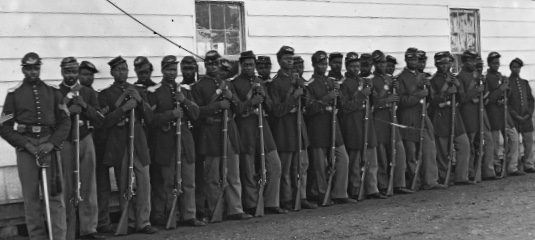

To borrow from our 16th president, its been 7 score and 17 years since the confederate attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina which began the war that would bring forth the conclusion of slavery in America. Early in 1863, in Boston, Massachusetts, recruitment began for a new regiment of infantry. The new unit at full strength would be 1,100 enlisted men with a normal slate of officers and officially joined the ranks of the union army in February as the 54th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

The new unit stood apart from other union formations for two reasons. First, it was the only unit that had no troops that were conscripted for service. The second, for the 54th, the issue of slavery was very personal; the unit was composed of the sons of men like Frederick Douglass, free slave and leader in the abolitionist movement, and men who knew firsthand what life as a slave in the south was like. The 54th would march south as our nation’s first all African-American enlisted regiment not to bring freedom to dark-skinned strangers but to bring freedom to friends and family still enslaved in areas controlled by the Confederate States of America.

The enlisted ranks may have been African-American, but the officers were white. Men like Colonel Robert G. Shaw who was a strong believer in the abolitionist movement volunteered to command the unit and by May 1863, the regiment was trained, equipped, and marching south to join the X Corps in South Carolina. Upon arrival, the men felt the first stings of their minority status in an army under regional command. The normal monthly pay for an enlisted solder was $13.00 per month. The 54th was told their pay was being cut to $10.00 per month with $3.00 to be withheld for uniforms, (which no other enlisted men had to pay), leaving them $7.00 per month. Once the news got back to Massachusetts, the state offered to pay the difference. The men on principle, regiment-wide boycotted their pay but continued to serve and fight.

In July 1863 the 54th would be involved in the second action at Fort Wagner, South Carolina. Confederate forces held a defensive position on James Island. On July 16, Confederate troops attacked the 54th while in a defensive position assuming the line would break. The regiment held its lines pushing back the assault loosing only 42 men. On the 18th, the 54th was called upon to spearhead the assault of Fort Wagner. By the end of the battle, the 54th was pushed back and the confederate troops continued to occupy Fort Wagner. Forty percent of the 54th‘s men were causalities that day. Their losses included Colonel Shaw. Although the 54th lost the action and the fort would remain in the hands of the Confederates until it was abandoned on September 7, 1863, the men of the 54th advanced the opportunities for African-Americans to serve in the Union by probing their courage and discipline on the battlefield. Soon after, the Union Army began recruiting additional African-American units, which would increase the numerical advantage of the union over the south.

The 54th would be back to combat strength and in action again in February 1864. Their next action was the Battle of Olustee, Florida. They still were not equally compensated for service and their regimental battle cry was “for Massachusetts and seven dollars a month.” Union forces attached the Confederate position but were pushed back by rifle and cannon-fire until the main body of the Union force retreated to Jacksonville. Shortly after nightfall the Confederate cavalry force attempted to attack the Union rear element composed of the 54th and the 35th United States Colored Troops. The attack failed and the Confederate forces were pushed back. After the Battle of Olustee in September of 1864 the Congress of the United States took action and African-American troops were paid equal to their white counterparts.

The 54th would see action in two additional battles, Honey Hill and Boykin’s Mill before the regiment would be disbanded on August 4, 1865. Construction began in 1884 ofna monument to the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry depicting Colonel Shaw at the top and was completed in Boston Common in 1898. On November 21, 2008, the Massachusetts National Guard reactivated the unit as military honors, now the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment.

The 54th, when faced with racism, acted not by protesting and conducting acts of civil disobedience by looting and destroying property, instead showed the content of their character by conducting themselves in a manner that set forth an example of how the men that observed them should conduct themselves.

How did the men of the 54th see our flag? Would they allow it to fall? Would they allow it to be stood upon? The actions of Sergeant William H. Carney at the Battle of Fort Wagner are very clear. When Sergeant Carney saw the flag-bearer mortally wounded and falling, he fought his way to him and took the unit’s American flag to safety. Later Sergeant Carney proudly told his men “that old flag never touched the ground.” President Abraham Lincoln presented Sergeant Carney the Medal of Honor for his bravery in action for preventing the American flag, given to the 54th, from falling in combat. Sergeant Carney was the first African-American recipient of the Medal of Honor.

Today, we stand during the National Anthem to remember the men of the 54th who did not have to serve but chose to serve to end slavery in America and died to make this nation move closer to ideals that all people are created equal. Today, we show respect to our nation’s flag to give respect to the memory of men like Sergeant Carney who were willing to die to prevent that “old flag” from touching the ground.